Ninety-five percent. That’s the failure rate for enterprise AI pilots according to MIT’s 2025 NANDA report. Not “underwhelmed executives” or “took longer than expected.” Outright failure. No measurable return. Project killed.

The other statistic cuts deeper. S&P Global found that 42% of companies abandoned most of their AI initiatives in 2025, up from 17% in 2024. The average organization scrapped 46% of proof-of-concepts before reaching production.

Something is fundamentally broken in how companies approach AI experimentation.

The Problem Isn’t the Technology

The MIT report pins failures on “fragile workflows, weak contextual learning, and misalignment with day-to-day operations.” Translation: the AI worked fine in testing but collapsed when it touched actual work.

On Hacker News, user morkalork captured the dynamic perfectly: “LLMs get you 80% of the way almost immediately but that last 20% is a complete tar pit and will wreck adoption.”

That last 20% kills pilots. A tool that handles 80% of cases brilliantly but fails on the remaining 20% creates more work than it saves because someone has to identify which cases fall into which bucket, verify the good outputs, fix the bad ones, and manage the cognitive overhead of a partially reliable system.

This is why pilots that “worked great in demos” crash in production. Demos show best cases. Production is all cases.

Choosing What to Pilot

Bad problem selection dooms pilots before they start. The question isn’t “what can AI do?” but “what specific problem costs us money or time that AI might solve better than alternatives?”

Good pilot problems share characteristics:

Measurable outcome. You can count something before and after. Time spent on tasks. Error rates. Volume produced. Revenue influenced. If you cannot put a number on it, you cannot evaluate whether the pilot succeeded.

Bounded scope. One team. One process. One use case. Pilots touching multiple departments introduce too many variables to interpret results, and the coordination overhead consumes resources that should support the actual experiment.

Frequent occurrence. The task happens often enough to generate meaningful data during the pilot period, which typically runs eight to twelve weeks.

Existing pain. People already complain about this problem, which means you are not convincing them something is broken but rather offering a potential fix for something they already want solved.

Low catastrophic risk. If AI makes mistakes, consequences are fixable. Do not pilot AI on tasks where errors cause major harm.

Examples that work: sales team prospect research, first-draft content creation for marketing, customer inquiry categorization, meeting summary generation.

Examples that fail: “use AI across the organization” (too broad), legal document review for critical matters (too risky), annual strategic planning (too infrequent to measure).

What Success Actually Looks Like

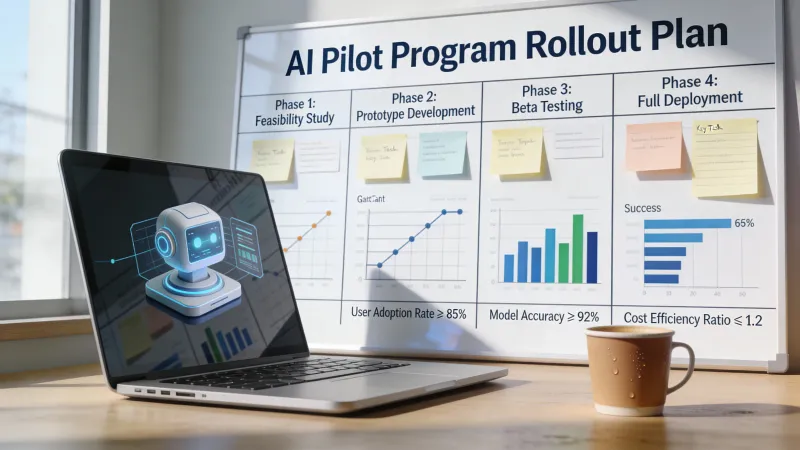

Write down exactly what success means before you start. This step gets skipped constantly, which is how pilots produce “it seemed helpful” instead of actual evidence.

Define primary metrics: the two or three most important things you will measure.

“Reduce average prospect research time from 45 minutes to under 20 minutes.”

“Increase content output from 4 pieces per week to 8 pieces per week with equivalent or better quality.”

“Achieve 85% accuracy on inquiry categorization compared to 72% current manual accuracy.”

Define secondary metrics that provide context: user satisfaction scores, downstream error rates, adoption percentage by week four.

Define failure indicators that tell you to stop early: quality scores falling below current baseline, less than 50% adoption after adequate training, significant security or compliance incidents.

Get stakeholder agreement on these criteria. Write them in a shared document. Revise only if circumstances change fundamentally, not because results disappoint.

The Right Size and Shape

Too small and results lack statistical significance. Too large and you have committed substantial resources to an unproven approach before knowing if it works.

Five to fifteen people is usually the sweet spot for team size. Enough to generate meaningful data, small enough to support adequately.

Eight to twelve weeks works for most pilots. Less than six weeks rarely allows for the adoption curve and behavior change. More than sixteen weeks loses focus and urgency.

One primary use case. Maybe a secondary one if closely related. Resist the urge to test everything at once because that is how you end up with results you cannot interpret and lessons you cannot apply.

For comparison approaches, you have options:

Before/after measurement works when you measure the same people before and after AI adoption. Simple, but does not account for other changes during the period.

Control groups work when some people use AI and some do not during the same period. Stronger evidence, but requires careful group matching and may create fairness concerns.

A/B within tasks works when the same person does some tasks with AI and some without. Best for high-volume repeatable tasks.

Choose based on your situation and the evidence level you need. If you will ask for major investment based on pilot results, a control group strengthens your case substantially.

Why People Quit Using the Tool

The most predictable pilot failure mode is adoption collapse. People try the tool, hit friction, and stop using it because nobody helps them through the rough patches.

User zoeysmithe on Hacker News described the typical scenario: “Staff asking ‘how can this actually help me,’ because they can’t get it to help them other than polishing emails.”

This is a support failure, not a tool failure. When people encounter problems and have no help, they give up. When they receive immediate assistance navigating obstacles, they push through to the point where the tool becomes valuable.

Support mechanisms that matter:

Structured initial training. Not “here’s the tool, figure it out” but actual learning sessions covering basics, common use cases, and tips from early testing.

Documentation people will use. Quick reference guides. Prompts that work for common scenarios. Troubleshooting steps for known issues.

Responsive help. Someone participants can reach with questions who responds in hours, not days.

Regular check-ins. Scheduled touchpoints to discuss what is working and what is not.

Peer learning channels. Ways for participants to share discoveries with each other.

The first two weeks are critical. Expect intensive support needs. Budget time accordingly. Front-loading support prevents the early frustration that kills pilots before they start producing useful data.

Honest Evaluation

The pilot ends. Time to assess.

Two common mistakes destroy evaluation value:

Declaring success prematurely. Some positive results do not mean the pilot worked. Compare against your predefined criteria, not against zero.

Explaining away failure. “It would have worked if…” is not success. Note the learning, but call failure what it is.

Questions for your evaluation:

Did we meet success criteria? Compare actual results to goals defined at the start. Be honest. “We achieved 70% of target metrics” is useful information.

What worked well? Specific tasks, use cases, or situations where AI delivered clear value.

What did not work? Tasks where AI was not helpful or made things worse. Be specific about why.

What surprised us? Unexpected positives or negatives, which often contain the most valuable learning.

What would we do differently? Both for the pilot process and for a potential broader rollout.

Is there a path to scaling? Based on results, does expansion make sense? What would need to change?

What is the recommendation? Clear next step: proceed to scaling, run another pilot with modifications, or discontinue.

Knowing When to Stop

Not every pilot should succeed. That is the point of piloting: learn cheaply what works and what does not before committing significant resources.

The MIT research found that companies running more pilots do not necessarily convert more to production. Mid-sized organizations move faster from pilot to full implementation. Large enterprises face a distinct transition gap where pilots succeed in isolation but fail to scale.

If your pilot misses success criteria, document the learning. Why did it not work? Tool limitations? Wrong use case? Implementation problems? Organizational resistance?

Distinguish failure types:

Wrong problem means pilot this solution on a different problem.

Wrong solution means pilot a different tool on this problem.

Wrong timing means try again when circumstances change.

Fundamentally does not work means stop investing.

Communicate honestly. “The pilot did not deliver expected results. Here is what we learned and what we recommend next.” Hiding failure prevents organizational learning and wastes the investment you made in running the experiment.

The Scale Decision

A successful pilot does not automatically mean successful scaling. The transition requires explicit planning.

Questions to answer before scaling:

Who is next? Which teams or functions should adopt after the pilot group? Prioritize based on likely impact and readiness.

What changes? Pilot conditions rarely match broad deployment. What processes need modification? What support structures need expansion?

What training is required? Your pilot group had intensive support. How do you train at scale?

What infrastructure is needed? IT requirements, security reviews, procurement processes, license expansion.

Who owns this ongoing? Someone needs accountability for continued success.

What is the budget? Scaling costs more than piloting. Build the business case from pilot data.

What is the timeline? Phased rollouts usually work better than big-bang deployment.

The MIT research found that purchasing AI tools from specialized vendors succeeds approximately 67% of the time, while internal builds succeed only one-third as often. Despite this data, many firms continue building proprietary systems internally. Consider this when planning your scaling approach.

The Verification Tax

One concept from the research deserves separate attention: the verification tax.

When AI outputs require checking, users spend more time validating than benefiting. If someone must review every AI-generated draft to catch errors, the time saved generating drafts may be consumed by review time. Worse, the cognitive load of constant verification wears people down.

Pilots must account for this. Measure not just output speed but total workflow time including verification. A tool that generates content in five minutes but requires thirty minutes of review is slower than the forty-minute manual process it replaced.

Solutions include better prompting, clearer use case boundaries, or accepting that some applications are not yet viable. But you cannot solve verification tax if you do not measure it, which is why tracking total task time matters more than tracking AI-assisted portions in isolation.

Making the Decision

At the end of your pilot, you face a choice. Scale, iterate, or stop.

Scale when you met success criteria, adoption was strong, the business case is clear, and you have a realistic path to broader deployment with adequate resources.

Iterate when results were mixed but promising, you learned what to change, and another pilot with modifications seems worthwhile.

Stop when results clearly missed criteria, the fundamental approach seems flawed rather than just the execution, or better alternatives exist.

The third option is harder than it sounds. Organizations develop attachment to initiatives. Pilots consume resources and create expectations. Admitting something did not work feels like failure even when it represents exactly the kind of learning pilots are supposed to produce.

But continuing to invest in approaches that piloting proved ineffective is the actual failure. The pilot did its job by providing information. Honor that information by making decisions based on what you learned rather than what you hoped.

Start Here

Ready to begin? Your checklist:

Choose your problem. One specific, measurable, AI-suitable challenge.

Define success criteria. Specific metrics with targets, written and agreed.

Select participants. Mixed group with time commitment and manager support.

Size appropriately. Five to fifteen people, eight to twelve weeks, one use case.

Plan the schedule. Clear phases with support front-loaded.

Build support mechanisms. Training, documentation, help contact, check-ins.

Set up tracking. Baseline measurements, weekly updates, documentation system.

Brief stakeholders. Everyone knows what you are testing and why.

Execute with attention. Support participants, track results, document learning.

Evaluate honestly. Against predefined criteria.

Communicate results. Clear findings and recommendations.

Decide next steps. Scale, modify, or stop.

AI pilots fail because of predictable reasons: wrong problems, unclear success criteria, inadequate support, and dishonest evaluation. Design yours to avoid these pitfalls.

The 5% of pilots that succeed are not lucky. They are well designed. And they start with clarity about what problem they are solving, what success looks like, and what they will do with the answer.