Your phone predicts words. It learns your habits. Type “see you” and it suggests “tomorrow” because you’ve sent that sequence a hundred times before.

Now imagine that same idea applied to essentially everything humans have ever written, everything available on the public internet, trained on hardware that costs millions of dollars and processes information in ways that strain the boundaries of what we thought computers could do. That is an LLM. Large Language Model. A machine trained to predict what comes next in a sequence of text, running at a scale that transforms a simple mechanism into something that feels almost like conversation.

The name breaks down cleanly. “Large” refers to size, both the training data (trillions of words) and the model itself (billions to trillions of adjustable parameters). “Language Model” describes the core function: modeling patterns in human language to predict probable continuations of any given text.

The Surprising Power of Guessing the Next Word

Here is what makes LLMs strange and wonderful and occasionally terrifying: they do not understand language in the way you understand it. They predict patterns.

When you ask an LLM to “write a professional email declining a meeting,” the model is not thinking about meetings or professionalism or your calendar constraints. It is calculating probabilities. Given these input tokens, what token most likely comes next? Then what token after that? The model repeats this prediction thousands of times until it has generated a complete response that, remarkably often, looks exactly like something a human would write.

Miguel Grinberg, a software developer who has written extensively about LLMs, puts it bluntly in his technical explainer: “All they can do is take some text you provide as input and guess what the next word (or more accurately, the next token) is going to be.”

That is it. Prediction. Statistics. Pattern matching at a scale that makes the results feel like magic.

But why does mere prediction produce coherent paragraphs? Why does guessing the next word result in something that answers questions, writes code, explains concepts, and occasionally makes you laugh?

The answer lies in what it takes to predict well. To accurately guess what word comes next in any possible sentence, you need to have absorbed an enormous amount of information about how language works, how ideas connect, how humans structure arguments and tell stories and express emotions. The compression required to predict accurately forces the model to develop internal representations that capture something resembling understanding, even if the mechanism underneath remains fundamentally different from human cognition.

How the Machinery Works

You type a question. The model responds in seconds. What happens in between?

First, your text gets converted into tokens. A token is a piece of a word, roughly three to four characters on average. The word “understanding” might become two or three tokens. Spaces and punctuation become tokens. Everything breaks down into these discrete units because neural networks work with numbers, not letters.

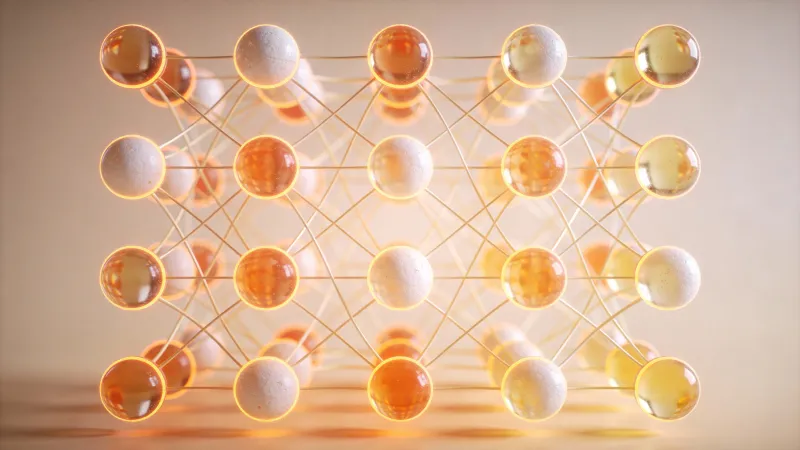

Those tokens get transformed into vectors, which are long lists of numbers that encode meaning and relationships. Each word or word-fragment becomes a point in a mathematical space where similar concepts cluster together. “King” and “queen” sit near each other in this space. So do “excellent” and “outstanding.” The model learned these positions by observing which words appear in similar contexts across its training data.

Then comes the attention mechanism, the breakthrough that made modern LLMs possible. Before 2017, language models processed words one at a time in sequence, which meant they struggled to connect ideas that were far apart in a sentence. The transformer architecture, introduced in the paper “Attention Is All You Need”, changed everything. Now the model can look at all the words simultaneously and determine which ones relate to which other words, regardless of distance.

As one explanation from Understanding AI describes it, words “look around” for other words that have relevant context and share information with one another.

This attention process repeats across many layers. Each layer refines the model’s understanding of the relationships between tokens. By the final layer, the model has built up a rich representation of the entire input and can calculate probability distributions over all possible next tokens.

The model picks a token. Adds it to the sequence. Runs everything through again to pick the next token. Repeats until the response is complete.

This is why LLMs can handle complex, nested sentences that would have baffled older systems. “The report that the analyst who was hired last month prepared for the executive team needs revision” is no problem. The model tracks that “needs” connects to “report” across all those intervening words.

Tokens, Parameters, Context Windows

Three terms come up constantly. Here is what they mean.

Tokens are the atomic units the model works with. Not quite words. Not quite characters. Something in between. A sentence like “I love chocolate chip cookies” might become five or six tokens. A page of text might be 300 tokens. This matters because models charge by the token and because there are limits to how many tokens a model can process at once.

Parameters are the adjustable numbers inside the model that get tuned during training. Think of them as the knobs and dials that determine how the model responds to any given input. GPT-4 reportedly has around 1.8 trillion parameters. More parameters generally means more capability, but also more computational cost. The relationship is not linear, and researchers keep finding ways to get more performance from fewer parameters.

Context window refers to how many tokens the model can consider at once, including both your input and its output. Older models had small windows, maybe a few thousand tokens. Modern models like Llama 4 Scout support up to 10 million tokens, enough to process entire books or codebases in a single conversation. Larger context windows mean the model can maintain coherent conversations over longer exchanges and analyze bigger documents.

Training: Where the Knowledge Comes From

LLMs learn from text. Vast quantities of text.

The training process works by showing the model billions of examples and asking it to predict what comes next. When it predicts incorrectly, the model adjusts its parameters slightly. Repeat this process across trillions of tokens of training data, using computing clusters that cost tens of millions of dollars to operate, and the model gradually develops the ability to predict continuations for essentially any text you might give it.

The training data typically includes books, websites, academic papers, code repositories, forums, and other publicly available text. The exact composition matters. Models trained on more code write better code. Models trained on more recent data have more current knowledge. Models trained on more diverse data handle a wider range of requests.

After this initial “pre-training” phase, most commercial models go through additional training phases. Fine-tuning on curated examples teaches the model to follow instructions and avoid harmful outputs. Reinforcement learning from human feedback helps the model produce responses that humans rate as helpful and appropriate. These additional steps shape the model’s personality and capabilities beyond raw prediction.

What the Limits Tell Us

The limitations of LLMs reveal what they actually are.

They hallucinate. They generate false information with perfect confidence. A lawyer famously submitted a legal brief written by ChatGPT that cited court cases that did not exist. The model had predicted plausible-sounding case names and citations because that is what legal briefs typically contain, but it was making things up.

Why does this happen? Because the model is predicting patterns, not accessing a database of verified facts. When the training data contains gaps or when the prompt creates unusual conditions, the model fills in blanks with whatever seems statistically likely. It has no mechanism for knowing whether its predictions correspond to reality.

As user Leftium noted in a Hacker News discussion about explaining LLMs: “Autocomplete seems to be the simplest way of explaining it is just fancy pattern recognition.”

Pattern recognition fails when the pattern requires actual knowledge of the world rather than knowledge of what text looks like.

They cannot verify. An LLM cannot check whether its claims are true because it has no access to external reality beyond what was in its training data. It cannot look something up. It cannot call an API to confirm a fact. It can only predict what words typically follow other words.

They are inconsistent. Ask the same question twice, get different answers. This is not a bug. Randomness is introduced deliberately to prevent the outputs from being boringly predictable. But it means you cannot rely on an LLM to give you the same response twice, which complicates any workflow where consistency matters.

They have knowledge cutoffs. Most models are trained on data up to a certain date. Anything after that date is unknown unless you explicitly provide it or the model has web search capabilities. GPT-5.2 models have a cutoff of August 2025, according to OpenAI. Events after that date simply do not exist for the model.

They struggle with math and logic. This might seem counterintuitive given how much capability they show elsewhere, but it follows directly from the prediction mechanism. Mathematics requires precise calculation, and LLMs are optimized for plausible continuation rather than accurate computation. They can mimic mathematical reasoning they saw in training data, but they are not actually computing.

A Different Kind of Intelligence

Andrej Karpathy, one of the researchers who helped build modern LLMs at OpenAI and Tesla, offered a clarifying perspective quoted on Simon Willison’s blog:

“It’s a bit sad and confusing that LLMs (‘Large Language Models’) have little to do with language; It’s just historical. They are highly general purpose technology for statistical modeling of token streams. A better name would be Autoregressive Transformers or something. They don’t care if the tokens happen to represent little text chunks. It could just as well be little image patches, audio chunks, action choices, molecules, or whatever.”

The implication is profound. LLMs are not language machines. They are pattern machines that happen to work extremely well on language because language has rich, learnable statistical structure. But the same architecture can model any sequential data.

This explains why LLMs can now handle images, audio, and video alongside text. The underlying mechanism is abstract enough to apply to any domain where patterns exist and where predicting what comes next is meaningful.

Why This Matters For You

If you work in any field that involves writing, analysis, communication, or information processing, LLMs are already changing what is possible.

They draft. They summarize. They brainstorm. They translate. They explain. They write code. They analyze documents. They do these things imperfectly, with caveats, requiring human oversight. But they do them fast, and the speed changes workflows.

A first draft that took two hours now takes two minutes. A document summary that required reading fifty pages now requires reading two paragraphs. A brainstorming session that produced ten ideas now produces a hundred, and even if ninety of them are mediocre, those extra ten good ones might include something you would never have thought of.

The catch is understanding what you are working with. An LLM is not a knowledgeable assistant who happens to be available at all hours. It is a prediction engine that generates plausible text. Sometimes that plausible text is exactly what you need. Sometimes it is confidently wrong. Knowing the difference requires you to understand the mechanism.

The Technology Keeps Moving

What is true in January 2026 will look different by December. The models are getting faster. They are getting cheaper. They are handling longer inputs. They are hallucinating less, though they still hallucinate. They are developing better reasoning capabilities, with dedicated “thinking” modes that work through problems step by step rather than jumping straight to answers.

Multimodal capabilities are expanding. The latest models from Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, and Meta handle images and audio natively. Models that once only processed text now analyze screenshots, interpret charts, and respond to voice input.

The fundamentals, however, remain stable. Prediction. Patterns. Scale. The models do not understand in the human sense. They approximate understanding through statistics applied at a scale that produces results indistinguishable from genuine comprehension in many practical contexts.

Whether that is “really” intelligence is a philosophical question. Whether it is useful is an empirical one. For most tasks involving language and text, the answer is increasingly yes.

The question is not whether to use these tools. It is how to use them effectively, understanding what they are and what they are not, so that the impressive parts help you and the limitations do not trip you up.

That is the real skill now. Not prompting tricks or secret techniques. Understanding the machine well enough to know when to trust it and when to double-check.