The cursor blinks. You hit enter. The AI responds with something that makes you want to close your laptop and take a walk.

We’ve all been there.

You asked for a professional email and got a rambling essay with six exclamation points. You wanted specific advice for your situation and received advice so generic it could apply to literally anyone on Earth. You requested a simple summary and got a philosophical treatise on the nature of summarization itself.

The natural instinct is to delete everything and start over, but that’s often the wrong move because it wastes the diagnostic information right in front of you. Bad output tells you something. The trick is figuring out what.

The Art of Reading Failure

A failed prompt is a message from the AI about what it understood, or more accurately, what it misunderstood.

When output goes wrong, it typically falls into recognizable patterns, and each pattern points to a different problem in how you structured your request. Generic output means missing context. Wrong format means unclear specification. Missed point means ambiguous phrasing.

One Hacker News commenter captured the frustration perfectly:

“But it essentially never makes what you expect… I’ve spent many hours on Midjourney”

Hours spent expecting one thing, getting another. This is the universal experience of working with AI systems, and it doesn’t mean you’re doing it wrong. It means you’re learning the language.

Vagueness Kills

The single most common failure mode is asking for something without defining what that something actually is.

“Write me a marketing email” gives the AI nothing to work with. Which audience? What product? What tone? What length? What should the reader do after reading it? Without answers, the AI fills in blanks with defaults, and defaults are by definition generic.

The fix isn’t adding more words. Bad prompts aren’t too short. They’re too vague. A ten-word prompt with three specific details will outperform a hundred-word prompt that never pins anything down.

Consider the difference between these two:

“Help me write an email to customers about our new feature.”

versus

“Write a 150-word email announcing our new scheduling feature to existing customers who’ve requested it. Tone: friendly, not salesy. Include one clear CTA to try the feature.”

The second prompt is longer but the length isn’t the point. Every added word does work. Nothing is filler. That’s the difference.

When Instructions Fight Each Other

Sometimes the AI isn’t confused. You are.

“Be comprehensive but keep it brief.” That’s a contradiction. You’re asking for two incompatible things, and the AI has to pick one, or worse, try to satisfy both and fail at both.

“Be creative but stick to the facts.” Another trap. Creativity implies invention; facts imply constraint. You can have creative presentation of facts, or factual grounding with creative flourishes, but telling the AI to be both without specifying how those interact produces confused output.

These contradictions are easy to write and hard to notice in your own prompts because you know what you meant. The AI doesn’t have access to your intentions, only your words.

Read your prompt as a hostile interpreter would. What could be misunderstood? What instructions might conflict? Where did you assume the AI would figure out what you really wanted?

The Overloaded Prompt

Another commenter on Hacker News nailed a related problem that plagues prompt engineers working on bigger systems:

“a 3,000-token system prompt isn’t ‘logic’, it’s legacy code that no one wants to touch. It’s brittle, hard to test, and expensive to run. It is Technical Debt.”

This applies to single prompts too. When you cram too much into one request, quality suffers everywhere.

“Write a blog post and create five social media posts for it and suggest email subject lines and also tell me what keywords to target” is not one task. It’s four tasks wearing a trench coat pretending to be one task. The AI will attempt all four and nail none.

Break it up. One thing at a time. Use the output from step one as input for step two. This is slower but produces dramatically better results.

Format Failures

You wanted a bulleted list. You got prose. You asked for JSON. You got a description of what the JSON would contain. You requested 200 words. You got 800.

Format failures happen when you assume the AI will guess correctly and it guesses wrong.

The solution is embarrassingly simple: say what format you want. Not “give me some ideas” but “give me 5 ideas as a numbered list, one sentence each.” Not “summarize this” but “summarize this in 3 bullet points totaling under 100 words.”

When the format is unusual or complex, show an example. AI systems are excellent at pattern matching, and showing a template of what you want is clearer than describing it.

The Telephone Game

Long conversations create a subtle failure mode that’s easy to miss.

You started with a clear goal. Fifteen exchanges later, context has drifted, earlier instructions have faded, and the AI has latched onto something you mentioned in passing as if it were the main point.

This is the telephone game playing out in real time. Information degrades with distance.

The fix is periodic context restatement, explicitly reminding the AI of the key parameters every few exchanges in a long conversation. “Quick reminder: we’re writing for [audience], aiming for [tone], and the goal is [specific outcome].” This feels redundant but prevents drift.

Factual Failures Are Different

When the AI makes stuff up, that’s a different category of problem entirely.

You can’t prompt your way out of hallucination because the AI isn’t failing to understand your instructions. It’s failing to know things. No amount of clever phrasing will make it remember a fact it never learned or generate accurate information about events after its training cutoff.

For factual content, the approach changes: you provide the facts. Give the AI the statistics, the quotes, the data points, the specific information that matters. Let it handle structure, flow, and presentation while you handle accuracy.

Asking an AI to “include relevant statistics” is asking it to guess what statistics might be real. Giving it “use these three statistics: [actual verified data]” keeps you in control of accuracy.

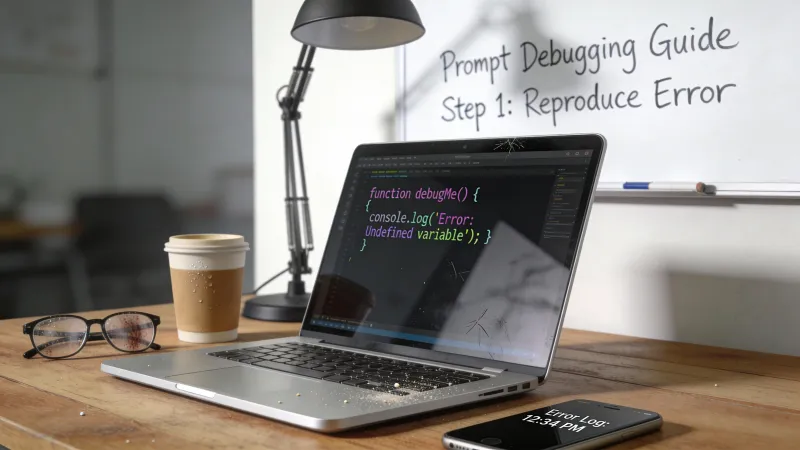

Diagnosis Before Surgery

When output fails, resist the urge to immediately rewrite. First, figure out what failed.

Is it generic? Look for missing context. Is the format wrong? Check if you specified format. Did it miss the point? Hunt for ambiguity in your phrasing. Is it contradictory? Examine your instructions for conflicts. Is it shallow? Consider whether you asked for depth.

Each failure type has a different fix, and applying the wrong fix wastes time while teaching you nothing.

This diagnostic step takes thirty seconds. Skipping it and rewriting from scratch takes five minutes and often recreates the same problem with different words.

The Iteration Loop

Once you identify the failure type, make one change. Test it. See what happens.

This feels tedious. It is tedious. It’s also faster than changing five things at once and having no idea which change helped or hurt.

Single-variable testing works in prompt engineering the same way it works in science and A/B testing. Change one thing, observe the result, adjust your hypothesis, repeat.

The temptation to rewrite everything comes from frustration, not strategy. Frustration produces action without learning. Systematic iteration produces learning you can apply to every future prompt.

When to Burn It Down

Sometimes iteration won’t save you.

If you’ve made four or five targeted fixes and nothing improves, the prompt may be structurally wrong. The core task might be unclear to you, not just to the AI. You might be asking for the wrong thing entirely.

Signs you should start over:

The AI seems genuinely confused about what you’re asking, not just giving suboptimal answers but appearing to address a completely different question. Your fixes keep shifting the problem rather than solving it. You realize mid-debugging that what you asked for isn’t actually what you need.

Starting over isn’t failure. Sometimes you need to write a bad prompt to discover what a good prompt for your actual goal would look like.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Prompt engineering is often unsatisfying because it feels like it should be easier than it is.

You’re writing in plain English. The AI understands English. Why doesn’t it just work?

Because natural language is inherently ambiguous, because what seems obvious to you isn’t obvious to a statistical model, because the AI is very good at producing plausible output that matches patterns in its training data and less good at understanding what you specifically need.

This isn’t going away. Better models will reduce some friction, but the fundamental challenge of communicating precise intent through imprecise language is a human problem, not a technology problem.

Learning to debug prompts is learning to communicate more precisely than normal conversation requires, and that skill transfers to human communication too. The engineer who writes good prompts writes clearer emails, creates better documentation, gives more useful feedback.

The cursor blinks. You try again. Eventually, it works. The question is whether you learned something in the process or just got lucky. Debugging gives you the learning. Random rewriting gives you the luck. One of those compounds over time.